27 Agosto, 22h

Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea (MNAC) – Museu do Chiado

Vertigo (Frac Île-de-France)

Curadoria de Xavier Franceschi

Duração da sessão 66’

Vertigo reúne um grupo de obras que provêm, na sua totalidade, da coleção do Frac da Île-de-France. De várias maneiras, entre contrastes muito intensos, o espectador mergulhará sucessivamente no divertimento, no deslumbramento, na dúvida ou no pavor.

Quer se trate da visita – muito acompanhada – a uma vivenda modernista (Ulla von Brandenburg), de jogos conceptuais simultaneamente simples e radicais (Pierre Bismuth), da visão de uma casa habitada por fantasmas (Alejandro Cesarco), de um retrato cujas tonalidades depressivas também revelam uma grande humanidade (Margaret Salmon) ou de um encontro que se transforma em pesadelo (Karen Cytter), os artistas propõem, com grande diversidade, experiências vertiginosas que não deixarão o espectador ileso…

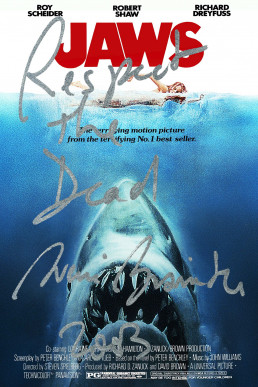

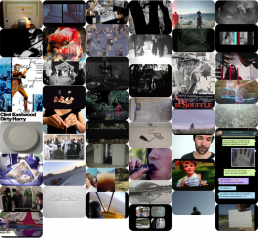

Pierre Bismuth, Respect the Dead (Jaws), 2001, 5’58’’

Se existe uma constante na obra de Pierre Bismuth, é de certo a maneira como o artista integra de várias formas o cinema no seu trabalho. Respect the Dead – respeitar os mortos – significa que é preciso atingir o silêncio e cessar toda a atividade durante algum tempo.

Pierre Bismuth aplica esta regra elementar de filosofia de vida a um conjunto de filmes entre os mais célebres na história do cinema, filmes que têm em comum o facto de que uma morte surge de repente – por vezes mesmo no próprio genérico – na narrativa. Daqui resulta algo sem lógica: quando a morte acontece, o filme é cortado e o genérico do filme é acrescentado.

Com Pierre Bismuth, que nos oferece de passagem a possibilidade de rever genéricos em todo o seu esplendor – para muitos verdadeiras obras-primas, os mortos podem, finalmente, viver em paz.

Ulla von Brandenburg, Singspiel, 2009, 14’45’’

Através dos seus filmes, desenhos, pinturas, esculturas e performances, Ulla von Brandenburg produz uma obra singular fundada sobre as questões de representação e de ilusão, invocando com profunda lógica o universo do teatro, do cinema e da literatura.

“Comédia musical minimalista” segundo os próprios termos da artista, este filme de 16mm, sonoro, a preto e branco, consiste num longo plano-sequência rodado em travelling nos espaços vazios da Villa Savoye (Vila Sabóia). Acompanhando esta errância na arquitetura modernista de Le Corbusier, a câmara cruza um certo número de personagens cuja atitude evidencia em todos os aspetos um profundo mal-estar. Uma mulher não consegue abrir uma porta, um jovem tenta desatar um molho de fitas, um homem – doente? Morto? – jaz por terra.

A uma arquitetura modernista, pura e radical, opõem-se o sofrimento e o tumulto da vida, quer nos sejam ou não explicitamente revelados. Em paralelo, pode vislumbrar-se aí, com plena justiça, uma evocação do destino da Villa Savoye e dos seus primeiros ocupantes…

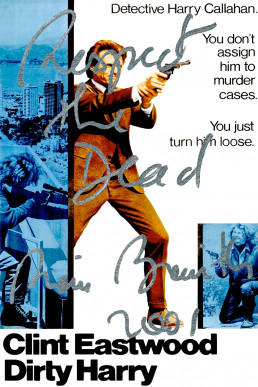

Pierre Bismuth, Respect the Dead (Dirty Harry), 2001, 2’27’’

Se existe uma constante na obra de Pierre Bismuth, é de certo a maneira como o artista integra de várias formas o cinema no seu trabalho. Respect the Dead – respeitar os mortos – significa que é preciso atingir o silêncio e cessar toda a atividade durante algum tempo.

Pierre Bismuth aplica esta regra elementar de filosofia de vida a um conjunto de filmes entre os mais célebres na história do cinema, filmes que têm em comum o facto de que uma morte surge de repente – por vezes mesmo no próprio genérico – na narrativa. Daqui resulta algo sem lógica: quando a morte acontece, o filme é cortado e o genérico do filme é acrescentado.

Com Pierre Bismuth, que nos oferece de passagem a possibilidade de rever genéricos em todo o seu esplendor – para muitos verdadeiras obras-primas, os mortos podem, finalmente, viver em paz.

Alejandro Cesarco, The Two Stories, 2009, 6’20’’

Na obra de Alejandro Cesarco, uma certa literatura – o nouveau roman, Roland Barthes – um certo cinema, o de Marguerite Duras – ocupam um lugar de primordial importância.

É, sem dúvida, precisamente a Marguerite Duras que Alejandro Cesarco se refere com The Two Stories, retomando uma narrativa de Felisberto Hernández, escritor e músico uruguaio do séc. XX, fundador do “fabulismo literário hispano-americano”.

De facto, o filme reveste-se explicitamente de uma forma – totalmente feita de lentidão, de concentração e de expectativa – desde sempre o traço distintivo da romancista/cineasta. O filme assenta essencialmente num anterior momento radical: uma câmara filma a preto e branco um espaço interior vazio, mas que anteriormente tinha sido o local de um certo acontecimento como nos é relatado em voz off. A câmara segue em diferido os movimentos anteriores do olhar do autor/leitor neste espaço, a partir de agora, vazio.

Deste modo e muito paradoxalmente, é pela ausência dos diferentes protagonistas, relegados para a condição de fantasmas, que Alejandro Cesarco nos faz reviver com intensidade, um evento que – parece – acontecer.

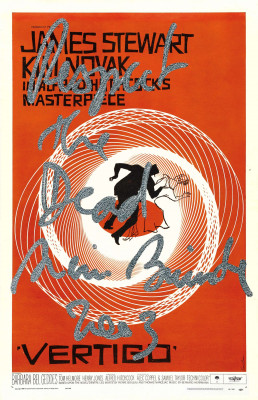

Pierre Bismuth, Respect the Dead (Vertigo), 2003, 4’49’’

Se existe uma constante na obra de Pierre Bismuth, é de certo a maneira como o artista integra de várias formas o cinema no seu trabalho. Respect the Dead – respeitar os mortos – significa que é preciso atingir o silêncio e cessar toda a atividade durante algum tempo.

Pierre Bismuth aplica esta regra elementar de filosofia de vida a um conjunto de filmes entre os mais célebres na história do cinema, filmes que têm em comum o facto de que uma morte surge de repente – por vezes mesmo no próprio genérico – na narrativa. Daqui resulta algo sem lógica: quando a morte acontece, o filme é cortado e o genérico do filme é acrescentado.

Com Pierre Bismuth, que nos oferece de passagem a possibilidade de rever genéricos em todo o seu esplendor – para muitos verdadeiras obras-primas, os mortos podem, finalmente, viver em paz.

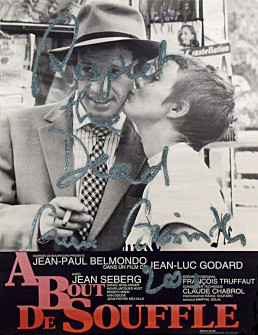

Pierre Bismuth, Respect the Dead (À Bout de Souffle), 2001, 5’20’’

Se existe uma constante na obra de Pierre Bismuth, é de certo a maneira como o artista integra de várias formas o cinema no seu trabalho. Respect the Dead – respeitar os mortos – significa que é preciso atingir o silêncio e cessar toda a atividade durante algum tempo.

Pierre Bismuth aplica esta regra elementar de filosofia de vida a um conjunto de filmes entre os mais célebres na história do cinema, filmes que têm em comum o facto de que uma morte surge de repente – por vezes mesmo no próprio genérico – na narrativa. Daqui resulta algo sem lógica: quando a morte acontece, o filme é cortado e o genérico do filme é acrescentado.

Com Pierre Bismuth, que nos oferece de passagem a possibilidade de rever genéricos em todo o seu esplendor – para muitos verdadeiras obras-primas, os mortos podem, finalmente, viver em paz.

Keren Cytter, Four Seasons, 2009, 12’

Em Four Seasons uma jovem, Lucy, introduz-se no apartamento de um homem com quem se encontra na casa de banho, queixando-se do barulho. Rapidamente surge um grave tumulto causado pela confusão entre esta personagem feminina e uma certa Stella que teria sido vítima de um crime violento perpetrado pelo homem. A repetição de um disco, a neve que cai na sala, um bolo e uma árvore de natal que se incendeiam pela ação do olhar… diversos fenómenos estranhos balizam o desenrolar de Four Seasons. Estes elementos irrompem num ambiente familiar e doméstico provocando um efeito de incongruência, de falta de lógica que tocam o fantástico, fazendo lembrar o universo de David Lynch.

Entre cinema-verdade e sitcom, home movie e telerrealidade, performance filmada e cinema de autor, Keren Cytter dá-nos uma sucessão de cenas onde o real parece constantemente disputá-lo à ficção.

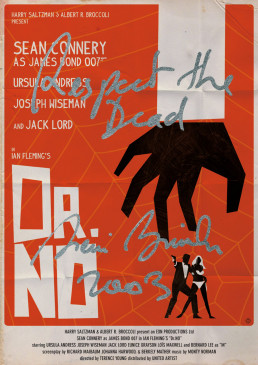

Pierre Bismuth, Respect the Dead (Dr. No), 2003, 4’07’’

Se existe uma constante na obra de Pierre Bismuth, é de certo a maneira como o artista integra de várias formas o cinema no seu trabalho. Respect the Dead – respeitar os mortos – significa que é preciso atingir o silêncio e cessar toda a atividade durante algum tempo.

Pierre Bismuth aplica esta regra elementar de filosofia de vida a um conjunto de filmes entre os mais célebres na história do cinema, filmes que têm em comum o facto de que uma morte surge de repente – por vezes mesmo no próprio genérico – na narrativa. Daqui resulta algo sem lógica: quando a morte acontece, o filme é cortado e o genérico do filme é acrescentado.

Com Pierre Bismuth, que nos oferece de passagem a possibilidade de rever genéricos em todo o seu esplendor – para muitos verdadeiras obras-primas, os mortos podem, finalmente, viver em paz.

Margaret Salmon, PS, 2010, 8’13’’

Os filmes de Margaret Salmon podem ser classificados como retratos inscritos numa tradição documental iniciada nos anos 1920, retratos que comportam uma dimensão de arquétipos e de universalidade.

Do mesmo modo, é para o domínio da ficção que são atirados os “não atores” que ela escolheu. Em PS, um homem idoso está no centro de uma disputa conjugal. A violência é transmitida pelos diálogos repetitivos, pelas discussões sem saída. Esta relação doentia exprime-se repetidamente através de gestos compulsivos da mão do homem na terra – planos “rurais” que fazem lembrar a América da depressão. No entanto, artifícios fotogénicos, tais como um espetáculo pirotécnico ou um plano através de um para-brisas cheio de gotas de água deslocam o filme, levam-no para outra dimensão, uma dimensão lírica.

Com Salmon, a procura da reprodução cinematográfica de uma realidade complexa é conduzida por dispositivos e figuras que rompem – ainda que fugazmente – com o naturalismo evidente do trabalho.

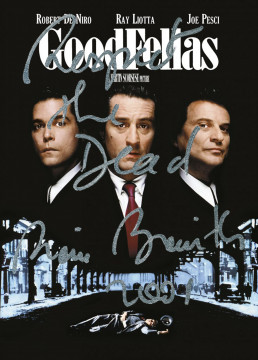

Pierre Bismuth, Respect the Dead (Goodfellas), 2001, 2’37’’

Se existe uma constante na obra de Pierre Bismuth, é de certo a maneira como o artista integra de várias formas o cinema no seu trabalho. Respect the Dead – respeitar os mortos – significa que é preciso atingir o silêncio e cessar toda a atividade durante algum tempo.

Pierre Bismuth aplica esta regra elementar de filosofia de vida a um conjunto de filmes entre os mais célebres na história do cinema, filmes que têm em comum o facto de que uma morte surge de repente – por vezes mesmo no próprio genérico – na narrativa. Daqui resulta algo sem lógica: quando a morte acontece, o filme é cortado e o genérico do filme é acrescentado.

Com Pierre Bismuth, que nos oferece de passagem a possibilidade de rever genéricos em todo o seu esplendor – para muitos verdadeiras obras-primas, os mortos podem, finalmente, viver em paz.

August 27, 10pm

Museu Nacional de Arte Contemporânea (MNAC) – Museu do Chiado

Vertigo (Frac Île-de-France)

Curatorship by Xavier Franceschi

Total running time 66’

Vertigo brings together a selection of works that come, in their entirety, from the collection of Frac Île-de-France. In many ways, in the midst of very intense contrasts, the viewer will dive successively into the fun, wonder, doubt or fear.

Whether being a tour – a guided one – by a modernist villa (Ulla von Brandenburg), conceptual games both simple and radical (Pierre Bismuth), the vision of a house inhabited by ghosts (Alejandro Cesarco), a portrait whose depressive character also shows a great humanity (Margaret Salmon) or an encounter which becomes a nightmare (Karen Cytter); the artists propose, with great diversity, dizzying experiences that will not leave the viewer unharmed…

Pierre Bismuth, Respect the Dead (Jaws), 2001, 5’58’’

If there is a constant in the work of Pierre Bismuth, it is certainly the artist’s way of integrating the film language in his work, within its multiplicity. Respect the Dead means being silent and ceasing all activity for a while.

Pierre Bismuth applies this basic rule of etiquette to a set of films among the most celebrated in the history of cinema, films having as common fact a death coming very early in the narrative – sometimes even during the opening credits. The result is logical: when death occurs, the film is cut and the end credits of the film are added.

With Pierre Bismuth, briefly offering us the possibility of viewing credit rolls in all their splendour – many of these are true masterpieces – the dead can finally live in peace.

Ulla von Brandenburg, Singspiel, 2009, 14’45’’

Through her films, drawings, paintings, sculptures and performances, Ulla Von Brandenburg produces a unique body of work based on issues of representation and illusion, evoking the universe of theater, cinema and literature.

“Minimalist Musical Comedy” according to the artist’s own terms, this 16mm film, black and white with sound, consists of a single traveling shot filmed in the empty spaces of the Villa Savoye. Accompanying this wandering in the modernist architecture of Le Corbusier, the camera crosses a number of characters whose attitude shows in many ways a deep malaise. A woman cannot open a door; a young man tries to untie some tapes; a man – sick? Dead? – lies on the ground.

Suffering and the turmoil of life, whether or not explicitly revealed to us, oppose a pure and radical modernist architecture. In parallel, we can see here an evocation of Villa Savoye’s fate and its first occupants…

Pierre Bismuth, Respect the Dead (Dirty Harry), 2001, 2’27’’

If there is a constant in the work of Pierre Bismuth, it is certainly the artist’s way of integrating the film language in his work, within its multiplicity. Respect the Dead means being silent and ceasing all activity for a while.

Pierre Bismuth applies this basic rule of etiquette to a set of films among the most celebrated in the history of cinema, films having as common fact a death coming very early in the narrative – sometimes even during the opening credits. The result is logical: when death occurs, the film is cut and the end credits of the film are added.

With Pierre Bismuth, briefly offering us the possibility of viewing credit rolls in all their splendour – many of these are true masterpieces – the dead can finally live in peace.

Alejandro Cesarco, The Two Stories, 2009, 6’20’’

In the work of Alejandro Cesarco, a certain literature – the nouveau roman, Roland Barthes – a certain cinema – that of Marguerite Duras – occupy a place of prime relevance.

It is, undoubtedly, precisely to Marguerite Duras that Alejandro Cesarco refers with The Two Stories, picking up a story of Felisberto Hernández, Uruguayan writer and musician of the 20th century, founder of the “Hispanic American literary fabulism”.

In fact, the film explicitly borrows a form – made of slowness, concentration and anticipation – the long-time hallmark of the writer and filmmaker Marguerite Duras. This film is based on a previous radical position: a camera films in black and white an empty interior that had previously been the site of a certain event told by a voice-over. The camera follows the previous movements of the author/reader’s gaze in this now empty space.

This way, paradoxically, it is by the absence of the protagonists, relegated to the status of ghosts, that Alejandro Cesarco makes us relive with intensity, an event that seems to actually occur.

Pierre Bismuth, Respect the Dead (Vertigo), 2003, 4’49’’

If there is a constant in the work of Pierre Bismuth, it is certainly the artist’s way of integrating the film language in his work, within its multiplicity. Respect the Dead means being silent and ceasing all activity for a while.

Pierre Bismuth applies this basic rule of etiquette to a set of films among the most celebrated in the history of cinema, films having as common fact a death coming very early in the narrative – sometimes even during the opening credits. The result is logical: when death occurs, the film is cut and the end credits of the film are added.

With Pierre Bismuth, briefly offering us the possibility of viewing credit rolls in all their splendour – many of these are true masterpieces – the dead can finally live in peace.

Pierre Bismuth, Respect the Dead (À Bout de Souffle), 2001, 5’20’’

If there is a constant in the work of Pierre Bismuth, it is certainly the artist’s way of integrating the film language in his work, within its multiplicity. Respect the Dead means being silent and ceasing all activity for a while.

Pierre Bismuth applies this basic rule of etiquette to a set of films among the most celebrated in the history of cinema, films having as common fact a death coming very early in the narrative – sometimes even during the opening credits. The result is logical: when death occurs, the film is cut and the end credits of the film are added.

With Pierre Bismuth, briefly offering us the possibility of viewing credit rolls in all their splendour – many of these are true masterpieces – the dead can finally live in peace.

Keren Cytter, Four Seasons, 2009, 12’

In Four Seasons, Lucy, a young woman, enters an apartment of a man while he is in the bathtub and complains about the noise. A severe turmoil quickly follows, caused by the confusion between this female character and a certain Stella who was the victim of a violent crime perpetrated by this man. The turning of a record, snowflakes falling in the living room, a cake and a Christmas tree catching fire by the mere action of looking… many strange phenomena mark out the course of Four Seasons. These elements erupt in a familiar and domestic environment, creating incongruous and absurd occurrences coming close to the fantastic, reminiscent of the Lynchian world.

Between cinéma vérité and sitcom, home movie and reality TV, filmed performance and auteur’s cinema, Keren Cytter gives us a succession of scenes where the reality and fiction are constantly at odds.

Pierre Bismuth, Respect the Dead (Dr. No), 2003, 4’07’’

If there is a constant in the work of Pierre Bismuth, it is certainly the artist’s way of integrating the film language in his work, within its multiplicity. Respect the Dead means being silent and ceasing all activity for a while.

Pierre Bismuth applies this basic rule of etiquette to a set of films among the most celebrated in the history of cinema, films having as common fact a death coming very early in the narrative – sometimes even during the opening credits. The result is logical: when death occurs, the film is cut and the end credits of the film are added.

With Pierre Bismuth, briefly offering us the possibility of viewing credit rolls in all their splendour – many of these are true masterpieces – the dead can finally live in peace.

Margaret Salmon, PS, 2010, 8’13’’

Margaret Salmon’s films can be classified as portraits in the documentary tradition that begun in the 1920s, portraits that contain an archetypal and universal dimension.

However, it is to the realm of fiction that are taken the “non-actors” she chose. In PS, an elderly man is seized at the centre of a marital dispute. Violence is transmitted by repetitive dialogues and dead-end altercations. This relational confinement is resumed by the compulsive gestures of human hands on earth – “rural” shots reminiscent of the Great Depression era in the US. However, photogenic devices, such as a firework display or a shot through a windshield full of water droplets, move the film to another dimension, a lyrical one.

With Salmon, the search of a filmic reproduction of a complex reality is driven by devices and figures that break – even briefly – with the apparent naturalism of the work.

Pierre Bismuth, Respect the Dead (Goodfellas), 2001, 2’37’’

If there is a constant in the work of Pierre Bismuth, it is certainly the artist’s way of integrating the film language in his work, within its multiplicity. Respect the Dead means being silent and ceasing all activity for a while.

Pierre Bismuth applies this basic rule of etiquette to a set of films among the most celebrated in the history of cinema, films having as common fact a death coming very early in the narrative – sometimes even during the opening credits. The result is logical: when death occurs, the film is cut and the end credits of the film are added.

With Pierre Bismuth, briefly offering us the possibility of viewing credit rolls in all their splendour – many of these are true masterpieces – the dead can finally live in peace.